Bluebirds are favorites of birders across North America for many reasons, including their beautiful blue colors, recognizable songs, and the eastern bluebird’s comeback story in some parts of the continent.

There are three species of bluebird, all native to North America: the eastern bluebird, the western bluebird, and the mountain bluebird. All are members of the genus Sialia in the thrush family, Turdidae.

Not to be confused with blue jays, members of the family Corvidae, bluebirds are relatively small, relatively blue birds.

Let’s get to know the three North American bluebird species.

Eastern Bluebird

Scientific name: Sialia sialis

The range of all three bluebird species overlaps somewhat, but residents of the eastern United States can be fairly certain of what species they’re seeing.

The eastern bluebird’s range stretches from the Atlantic Coast to the Great Plains, mostly stopping its westward expansion just before reaching the Rocky Mountains, though they do live year-round in Central America up into southern Arizona and winter in southern New Mexico and western Texas.

Southern birds are year-round residents with populations moving into southern Canada and the more northern states of the upper Midwest and Northeast during the breeding season.

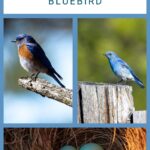

Males are a vibrant blue on top with a subdued orange covering the throat and the rest of the underside.

Females have white bellies, orangey-brown sides and chests, and gray heads. Their wings are a muted blue color.

All three bluebird species typically measure between six and eight inches long, according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds.

Those particular numbers likely don’t tell you that much when identifying a bird in the field, even to many experienced birders, so you can think of a bluebird as a little bit bigger than a sparrow or a finch but noticeably smaller than other familiar backyard birds like cardinals or robins.

Mountain bluebird

Scientific name: Sialia currucoides

The mountain bluebird has a pretty wide breeding range that extends from Alaska and Canada down to California, New Mexico, and Arizona, where they may also spend the winters.

Their non-breeding range also encompasses parts of Mexico and the lower Great Plains.

Adult males feature beautiful shades of blue covering almost their entire bodies, a little deeper on the wings and cap and lighter underneath.

Females are mostly a dull tan color, with a little bit of blue poking out near the tail and bottom of the wings.

Western Bluebird

Scientific name: Sialia mexicana

The most sparse geographic range of the three bluebird species is that of the western bluebird, with a spotty breeding range that includes parts of the Pacific Northwest, California, Mexico, and the Southwest.

Their range doesn’t overlap too much with the eastern bluebird, their closest doppelganger, but where it does, the first thing you’ll want to look for is the throat color.

Western bluebirds have a blue throat that dips lower than the neckline, while eastern bluebirds’ rusty orange coloration meets the blue head much further up the body.

People in most locations won’t have to worry about this, as their ranges mostly only overlap in parts of the southwest such as Mexico, Texas, and New Mexico.

Female western bluebirds generally have more orange to their chest than the tan mountain bluebird female, though they can look pretty similar in less colorful females.

They are fairly similar to eastern bluebird females, with throats of a darker gray than the typically lighter eastern bluebird.

Habitat

All three bluebird species are common in mostly open spaces. They wouldn’t be out of place in parks, fields, meadows, backyards, or any other lightly wooded area.

They are cavity nesters, so they do require at least sparse tree cover to nest unless an alternative option, like a nest box, is provided.

Many people put up nest boxes to take the place of traditional tree cavities in hopes of attracting a nesting bluebird pair to their backyards. You might also see nest boxes in open public natural areas to provide bluebirds and other cavity nesters with cover.

Bluebird Nesting Habits and Eggs

If you’ve ever been out for a walk and seen nest boxes set up in the middle of a meadow or field, there’s a decent chance that it was intended for bluebirds.

Just because it was intended for bluebirds doesn’t mean that’s who will move in, however. And the other birds just might be blue, adding to any potential confusion.

Tree swallows and purple martins are among the birds that may take up residence in nesting boxes across North America, and their blue coloring can trick birdwatchers at first glance. Look for their pointed wings to help you identify them in flight.

Bluebird eggs are typically known to be blue, although some may be more white. According to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, between five and nine percent of bluebird eggs are white.

The blue color of the eggs, which is not unique to bluebirds, is caused by the pigment biliverdin, which is also what gives human bruises their blue-green color.

According to Hitchcock Center for the Environment Environmental Educator Katie Koerten, there are still some questions about why eggs are blue, with studies looking into what color birds see the eggs as and correlating it to the mother’s health, among other potential explanations.

One of the most prevalent answers of why bluebird eggs are blue relates to sun protection, with Koerten writing that the color blue may balance UV protection with being light enough to not cause eggs to overheat.

However, as Koerten notes, cavity nesters like bluebirds wouldn’t really need UV protection, as they’re almost always shielded from the sun.

Incubation usually takes between 13 and 20 days, according to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, with incubation time impacted by how often food is brought by the male to the female and the temperature in the box. Low temperatures and less food extend incubation time.

According to the Georgia DNR, hatchlings open their eyes at eight days old and fly for the first time between 17 and 21 days old.

Conservation Status

After several threats in the 1900s, eastern bluebird numbers have been on the rise for several decades.

Between habitat loss, pesticide use, and the growing number of competitive cavity nesters like European starlings and house sparrows, bluebird populations were struggling. But between 1980 and 2010, eastern bluebird populations increased by about three percent per year, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

Expanding that timeframe a bit more, eastern bluebird populations grew about 1.5 percent annually from 1966 to 2015. In the same time period, western bluebird numbers increased by 0.7 percent annually, according to the survey.

Mountain bluebirds haven’t seen quite the same trend, as mountain bluebirds saw an average decline of half a percent from 1966 to 2015.

Some local populations may have seen more drastic trends one way or the other but on the whole, all three North American bluebird species were considered to be of “least concern” in their most recent IUCN Red List assessments.

Diet and Behavior

Sometimes, people will bemoan the fact that they never see bluebirds in their yards, despite living in one of the species’ breeding ranges and having feeders up all year. In many cases, this is because bluebirds don’t typically visit backyard seed feeders.

They don’t usually eat seeds unless out of necessity. They feed mostly on insects and fruit, so offering up mealworms (alive or dried) gives you a much better chance of seeing one at a feeder.

For a full guide to what bluebirds eat, click here.

Sounds

Listen to some of the calls and sounds of each of North America’s three resident bluebirds here:

Eastern bluebird call:

Eastern bluebird song:

Western bluebird call:

Western bluebird song:

Mountain bluebird call:

Mountain bluebird song:

Frequently asked questions

Are bluebirds territorial?

Eastern bluebirds are “extremely territorial,” often fighting over nest cavities, according to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.