Few things are more heartbreaking than finding a bluebird nest destroyed by house sparrows. If you’ve put up nest boxes hoping to attract these gentle native birds, only to see aggressive sparrows take over, you’re not alone. The good news? With a few strategic changes, you can protect your bluebirds and give them a safe place to raise their young.

Why House Sparrows Push Out Bluebirds

Save this article for later so you don't lose it. Enter your email and I'll send it to you now—plus you'll get my favorite backyard birding tips delivered to your inbox.

Birdfy Solar Powered Bird House with Camera

Check PriceHouse sparrows aren’t just competing for space—they’re an invasive species that actively destroys the nests of native birds. Introduced to North America in the 1850s, these aggressive non-natives will peck bluebird eggs to pieces, kill nestlings, and even attack adult bluebirds inside nest boxes. It’s brutal, but understanding this behavior is the first step in protecting the birds you’re trying to help.

Unlike most native birds that simply compete for territory, house sparrows see nest boxes as their own and defend them violently. They’re cavity nesters too, which means they’re looking for exactly the same housing bluebirds need. Because they’re year-round residents in most areas and breed multiple times per season, they often claim boxes early and refuse to leave. The result? Bluebirds get pushed out before they even have a chance to nest.

This isn’t a case of “letting nature take its course”—house sparrows are an introduced problem, and managing them is part of responsible bluebird stewardship. The more you know about their habits, the better equipped you’ll be to keep your boxes safe for native species.

Choose the Right Nest Box Design

Your first line of defense starts before you even hang a box. The right design can make a huge difference in who moves in. Standard bluebird boxes work well, but there are specific features that help discourage house sparrows while still welcoming bluebirds.

Start with the entrance hole size. A 1.5-inch hole is traditional for bluebird boxes, but house sparrows fit through it easily. If you size down to 1 to 1.25 inches, you’ll still accommodate bluebirds—they’re smaller than most people think—while making it harder for the chunkier house sparrows to enter. Some experienced bluebirders swear by slot-style entrances instead of round holes. These vertical openings measure about 1.25 inches wide by 2.5 inches tall, and bluebirds adapt to them quickly while sparrows seem less interested.

Box placement matters too. Avoid mounting boxes directly on buildings, barns, or near human structures where house sparrows love to congregate. Instead, place them in open areas at least 100 yards from buildings—bluebirds prefer open habitat with scattered trees anyway, while sparrows thrive near human activity. This simple shift in location can dramatically reduce sparrow interest.

Consider boxes with deeper interiors as well. A box that’s at least 8 to 10 inches from the entrance hole to the floor makes it harder for sparrows to reach in and destroy eggs or nestlings. Every small design choice adds up to better protection.

Monitor and Remove Sparrow Nests Quickly

Here’s the truth about managing house sparrows: you need to check your boxes regularly. Passive monitoring won’t cut it. Plan to inspect your nest boxes at least twice a week during nesting season—more often if you’re dealing with persistent sparrows.

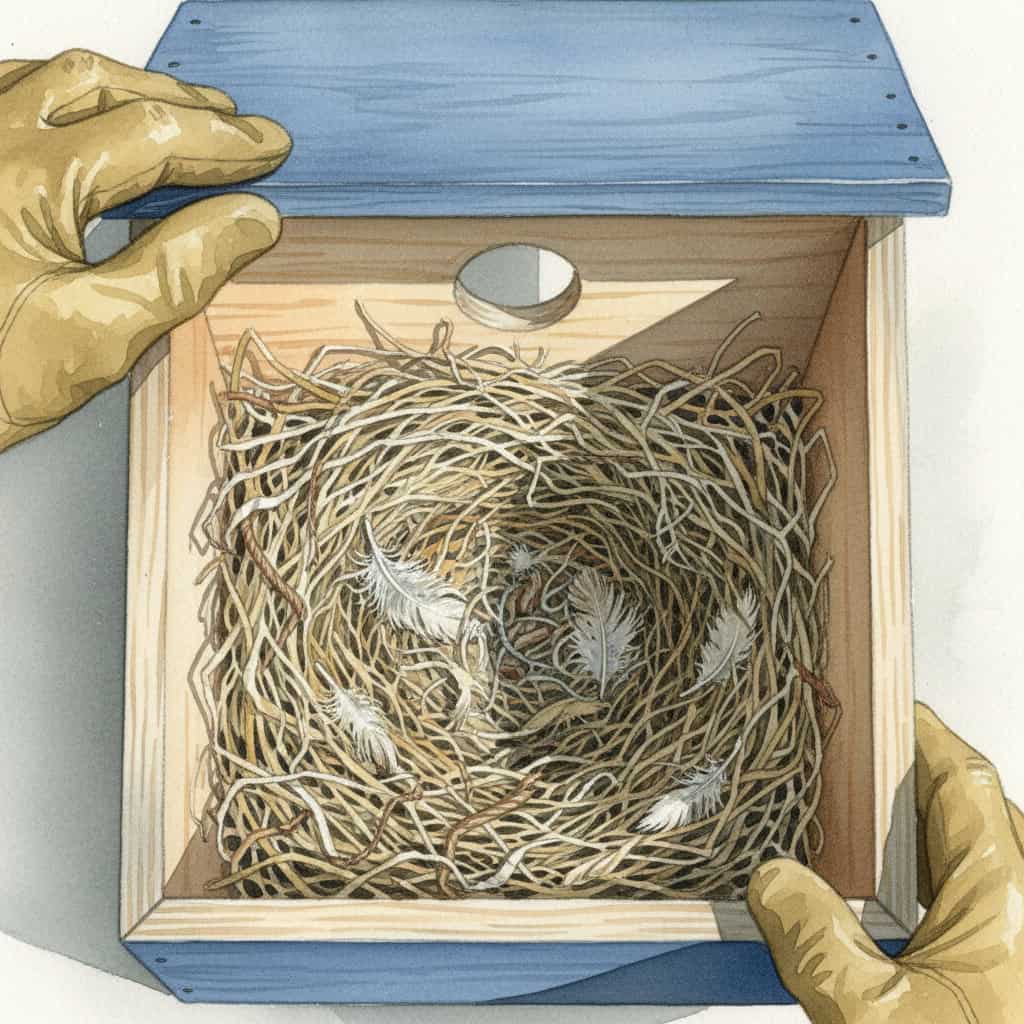

House sparrow nests are easy to identify. They’re messy, bulky constructions made mostly of dried grasses, feathers, and often bits of trash like string or paper. Unlike the tidy, cup-shaped nests bluebirds build with fine grasses and pine needles, sparrow nests fill the entire box with loose material and have a domed or rounded appearance. If you spot one starting to form, remove it immediately.

Don’t hesitate—house sparrows are not protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act because they’re an invasive species. You’re legally allowed to remove their nests, eggs, and even the birds themselves if necessary. Toss out any nesting material you find, and if eggs are present, remove those too. The key is consistency. If sparrows keep finding their nests destroyed, they’ll often move on to find an easier location.

Keep boxes empty between removals. An empty box is less appealing to sparrows trying to rebuild than one with even partial nesting material. Some bluebird landlords check boxes daily when sparrows are particularly persistent, and that vigilance pays off. Once bluebirds claim a box and start laying eggs, your monitoring becomes even more critical—but you’ll also have more options for deterrents.

Use Simple Deterrents Like Fishing Line and Spookers

Get our free Hummingbird Attraction Guide! Plus, we'll send you our best tips for attracting more birds to your yard.

Sometimes the simplest solutions work best. Two of the most effective house sparrow deterrents require nothing more than fishing line or a few household materials, and they won’t bother your bluebirds at all.

The fishing line method is surprisingly effective. Attach monofilament fishing line (about 10-12 pound test) across the roof of your nest box in a crisscross pattern, or dangle short lengths from the roof overhang so they hang just in front of the entrance hole. House sparrows are wary of anything touching their backs or wings as they enter, and these nearly invisible lines make them uncomfortable. Bluebirds, on the other hand, seem unbothered and slip right past. You can also try the “Van Ert” trap design, which uses fishing line in a specific configuration to catch sparrows while leaving bluebirds alone—though this requires more setup.

Sparrow spookers are even more dramatic. Wait until your bluebirds have laid at least one egg—this is important, because spookers can sometimes deter bluebirds if installed too early. Once eggs are present, bluebirds are committed and won’t abandon the nest. At that point, you can add a sparrow spooker: a device that sits on top of the box with long arms extending outward, decorated with metallic Mylar tape or reflective streamers that flutter in the wind.

House sparrows are deeply suspicious of the movement and flash, while nesting bluebirds quickly learn to ignore it. The shimmering, unpredictable motion is enough to keep sparrows from entering the box to attack eggs or nestlings. You can build a simple spooker from a wire coat hanger, zip ties, and Mylar party streamers for just a few dollars. Install it as soon as you confirm bluebird eggs, and leave it up until the babies fledge.

Both methods work because they exploit house sparrows’ cautious nature around unfamiliar movement or texture. They’re not foolproof, but combined with regular monitoring, they significantly reduce the risk of attack.

Set Up a Dummy Box Trap

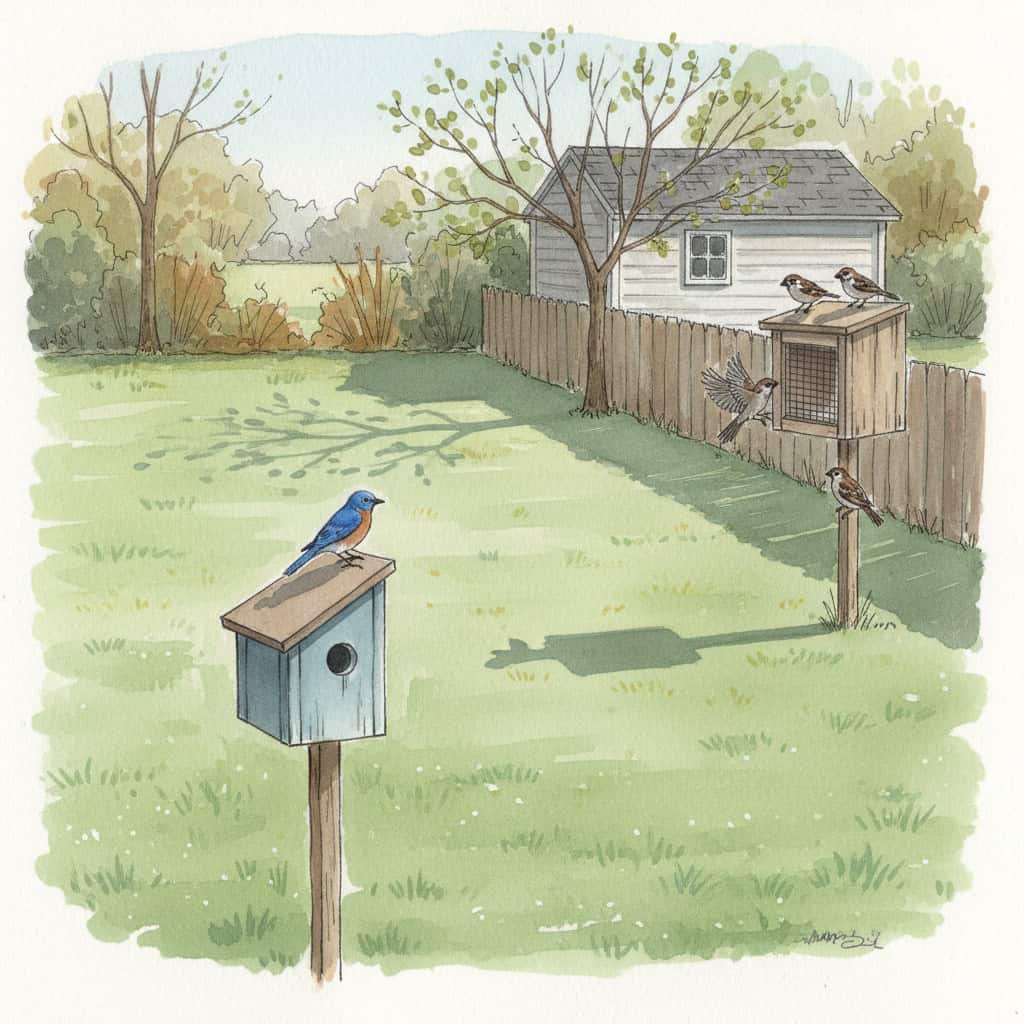

If you’re dealing with a particularly stubborn pair of house sparrows, a decoy box can work wonders. The concept is simple: give the sparrows what they think they want, somewhere away from your bluebird boxes.

Place a dummy box—also called a “sparrow trap box”—at least 50 to 100 feet away from your active bluebird boxes, ideally closer to buildings or structures where sparrows naturally congregate. This box should look appealing to sparrows: mount it on a pole or fence near human activity, use a standard 1.5-inch entrance hole, and let the sparrows discover it.

Here’s where monitoring becomes essential. Check the dummy box frequently. If sparrows start building, you have a choice: you can continuously remove the nest to frustrate them, or you can use the box as a trap. Sparrow traps (which fit inside nest boxes) are legal and humane when checked regularly, and they allow you to remove house sparrows from the area entirely. This is the most effective long-term solution if you have repeat offenders.

The key is never to ignore a dummy box. If you let sparrows successfully nest in it, you’ve just created more sparrows for next season. Used correctly, though, a decoy box draws attention away from your bluebird houses and gives you a centralized place to manage the problem. Some bluebird trail operators use multiple dummy boxes to create a “sparrow sink” that protects dozens of bluebird boxes across a property.

Adjust Feeders to Favor Bluebirds

Your bird feeders might be part of the problem. House sparrows are opportunistic feeders that love cheap, easy meals—and many common feeder setups are like an all-you-can-eat buffet for them. A few smart changes can reduce sparrow numbers around your yard while still feeding the birds you want to see.

First, switch your seed. House sparrows go crazy for cracked corn, millet, and cheap mixed seed blends. If you’re using those, you’re rolling out the welcome mat. Instead, offer striped sunflower seeds (not the smaller black oil sunflower that sparrows love), safflower, or nyjer thistle. Cardinals, finches, and other natives enjoy these, but house sparrows find them less appealing. The switch alone can reduce sparrow traffic dramatically.

For bluebirds specifically, skip the seed entirely and offer mealworms in a dedicated feeder. Bluebirds are primarily insectivores and will readily take live or dried mealworms, especially during nesting season when they’re feeding hungry babies. House sparrows might try them, but they’re far less interested than bluebirds and other insect-loving natives like chickadees and nuthatches.

Add baffles and guards to your feeders to make access harder for sparrows, which tend to be less agile than native birds. A simple dome baffle above a hanging feeder or a cage-style feeder that only allows smaller birds through can reduce sparrow dominance at feeding stations. Less food availability means fewer sparrows sticking around—and fewer sparrows near your nest boxes.

Make Your Yard Bluebird-Friendly

The best long-term strategy for keeping bluebirds around is to create habitat they love—and that house sparrows find less attractive. When your yard meets bluebirds’ needs for food, water, and shelter, they’re more likely to claim nest boxes quickly and defend them successfully.

Start with open space. Bluebirds prefer large lawns or meadows with scattered trees and low ground cover where they can hunt insects. Unlike house sparrows that cluster around buildings and dense shrubs, bluebirds want clear sightlines and hunting grounds. If you can maintain short grass or natural meadow areas, you’re already ahead. Even a modest yard with open areas and a few perches works well.

Native plants make a huge difference. Berry-producing shrubs like dogwood, serviceberry, sumac, and elderberry provide natural food sources that bluebirds rely on, especially in fall and winter when insects are scarce. These plants also support the insects that bluebirds feed their nestlings. House sparrows, being primarily seed-eaters and human-affiliated birds, don’t benefit as much from this kind of native habitat. The more native your landscape, the more it favors bluebirds over invasives.

Fresh water is essential. A birdbath or shallow water feature gives bluebirds a place to drink and bathe—and in dry periods, it’s a major attraction. Keep the water clean and shallow (1 to 2 inches deep), and place it in an open area where bluebirds feel safe from predators. Moving water from a dripper or fountain is even better, and it’ll attract a wider variety of natives.

Finally, think about box placement as part of the bigger picture. Position your bluebird boxes facing open areas, away from thick brush and buildings. Mount them on poles with predator guards, and space multiple boxes at least 100 yards apart to reduce competition—or try pairing boxes closer together, which sometimes allows bluebirds and tree swallows to nest near each other while keeping sparrows out.

When you combine smart box design, active monitoring, effective deterrents, and quality habitat, you create an environment where bluebirds thrive and house sparrows struggle to gain a foothold. It takes some effort, especially at first, but watching a family of bluebirds successfully fledge from your boxes makes every bit of it worthwhile. You’re not just putting up a box—you’re actively supporting native wildlife and reversing some of the damage invasive species have done. That’s something to feel good about.

Happy birding!